17 Mar 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Going head with the general election amidst a virus outbreak is not just plain dangerous. It could trigger an existential threat

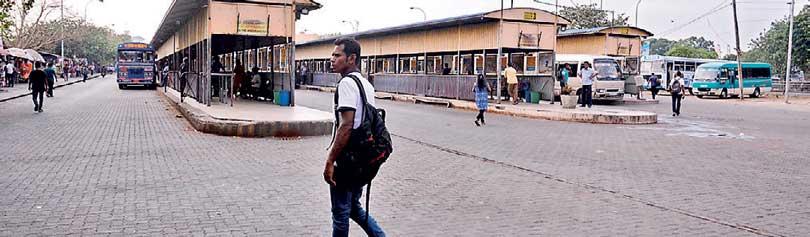

Picture shows the deserted Pettah bus stand, as the govt. advised people against mass gathering due to coronavirus spread.

PIC BY Pradeep Pathirana

It does not take much persuasion to convince someone that holding a countrywide snap parliamentary polls on the eve of a global Coronavirus pandemic is a dangerous idea. More so when the local health officials advocate social distancing. Public gatherings are discouraged. Schools are closed and unnerved public are panic buying. And if the global trend of the rapid spread of the virus is anything, Sri Lanka, now with 18 proven cases (as of yesterday noon) and 1723 returnees from abroad in quarantine is bound for a leap in the patients and a looming health emergency.

It does not take much persuasion to convince someone that holding a countrywide snap parliamentary polls on the eve of a global Coronavirus pandemic is a dangerous idea. More so when the local health officials advocate social distancing. Public gatherings are discouraged. Schools are closed and unnerved public are panic buying. And if the global trend of the rapid spread of the virus is anything, Sri Lanka, now with 18 proven cases (as of yesterday noon) and 1723 returnees from abroad in quarantine is bound for a leap in the patients and a looming health emergency.

Given the current circumstances, avoiding the internal/communal transmission of the virus and plan and implement policies to that end is the best that the government could do to avert a major outbreak. However, the government seems to be distracted by other competing priorities. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has said that the elections will go ahead as planned. Fittingly, he said so in a video conference with fellow South Asian leaders on the regional preparedness to coronavirus.

To understand how fatalistic this decision could turn out to be, have a glance at Sri Lanka’s current status in the epidemic. There are 18 cases in hospitals, all but one have contracted the virus from a foreign source, and most of them while abroad. The overwhelming majority are Sri Lankans who recently returned from Italy and were sent to a military administered quarantine facility, two others are also from Europe. There is also a local tour guide who contracted the virus from an Italian tour group. A colleague caught the bug.

In other words, Sri Lanka’s coronavirus cases are imported. Except, in the instances of the two tour guides, there are no known cases of internal transmission. That is the silver line in the dark cloud. If the country manages to send Sri Lankan returnees and a dwindling number of foreign visitors to mandatory quarantine, Sri Lanka has quite an opportunity to avoid the communal spread of the virus.

However, there are reservations whether the quarantine of returnees was implemented too late. There are also concerns that some of the returnees might have evaded the quarantine process. These problems are understood. Sri Lanka can not replicate an aggressive and at times thuggish forced measures akin to China, without triggering a much larger upheaval. Protests at the airport early this week are proof.

The government itself was trapped between justifiable concerns of an economic fallout due to the loss of tourism revenue and the potential health hazard due to the arrivals from Europe - until it finally shut the door and suspended flights.

Probably some cases might have leaked to the community. The health workers and the military are now tracing those who returned from Italy during the last two weeks before the mandatory quarantine was implemented. The high number positive cases from Italian returnees - which outnumber the per capita cases even in Italy, the worst hit in Europe, should be a cause for concerns. Health officials should investigate whether the majority caught the bug while in Italy, in the flight or at the quarantine centres back in Sri Lanka.

Italy itself offers an abject lesson of the alarming propensity of the communal spread of the virus. Three weeks back, Italy had just 200 cases. As of Sunday, there were 24,747 positive cases, up from 21,157 the previous day. A total of 1,809 had died so far. Italy has more per capita positive cases and deaths than China, where the virus is thought to have originated and had first major spread.

As of yesterday, global coronavirus pandemic has killed, 6500 people; over 165,000 positive cases were reported and the number of cases outside side (87,000) has surpassed the Chinese toll of 80,860.

Travel restrictions and mandatory quarantine of arrivals currently in place would greatly reduce the risk of the virus spreading from foreign sources. However, whether the virus has already leaked to the community through foreign arrivals is a possibility. If that happens, then there is the danger of what epidemiologists call silent chains of transmission.

Sri Lanka’s challenge is to trace these silent chains and disrupt the transmission of the disease. Until then, social distancing, and limiting or avoiding public space, (and practising good hygiene) would keep the disease from spreading. However, elections do exactly the opposite. They provide the fertile set up for transmission, multiplication of silent carriers, and would drive the country towards a major communal spread of the virus.

This does not need to sound unduly political. But, this election which was announced six months before the expiration of the term of Parliament should not have been called, in the first place. Because by the time it was announced on March 1, the wider implication and spread of the virus across the continents were already warned.

In each country it made an initial impact, it gathered momentum and size like a snowball sliding down an icy mountain. Epidemiologists warned the worst. Sri Lanka itself set up its own Corona Task Force in January and evacuated Sri Lankan students from the virus hit Wuhan in the early February. The first case found in the country, a Chinese female from Wuhan was tested positive in January. Since then for over a month, there had been no additional cases, until the sudden leap in numbers last week. The absence of new cases might have given a sense of false security. However, if the president had asked his advisors (and if they were not usual yes men and women) they might have apprised him of the ramifications of the election on the eve of a virus outbreak.

Now, if anything, Sri Lanka is at the foothills of the mountain. If it can avoid the community spread, we can escape the worst. Elections would complicate the measures to combat the virus spread. The President said the election campaign would be low key and the political parties would eschew mass rallies. That is not how you conduct general elections in this country. Also, a lukewarm campaign with possible restrictions on mass gathering would create an uneven level playing field for the government at the disadvantage of the other political parties.

The stakes of the general elections are too high too, especially when the government is canvassing to win a two-thirds majority in Parliament to amend the constitution. This election, if held under current conditions would not only pose a Himalayan scale national health hazard. It would also be a travesty in electoral democracy.

Also, don’t forget elections are polarising affairs. The typical electioneering in the Sri Lankan style with the full disposal of social media rumours and politically tinted slants would damage what is most needed for the government to mobilize the public to fight the virus: i.e. the public trust in the government. Though the Sri Lankans would hopefully rally together at a time of adversity, political polarization courtesy the election would drag them apart. Things could get ugly and dangerous.

The President should ask himself whether this is worth the cost. He might not have expected this when he called for snap elections. But, now he should know what is in the store for the country if he proceeds ahead with an ill-timed general election. He might be hoping that the status quo would remain. But it is a dangerous gamble that could have a dangerous payoff.

He should take a step back and revoke the gazette notification that announced the dissolution of Parliament and called snap elections. So that Parliament can go on for remainder and the government can mobilize its energies to fight the virus and repair the economic damage of the global outbreak.

Follow @Ranga Jayasuriya on Twitter

27 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

27 Dec 2024 4 hours ago