04 May 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

India is in the grips of an avoidable catastrophe. In a country that prides itself as the pharmacy to the world, patients are gasping for breath and crematoriums are running out of place. While an unprecedented second wave of the Coronavirus pandemic had been building up, its Prime Minister, Narendra Modi indulged most of his time in a vindictive election campaign. His political strategist and home affairs minister Amit Shah, spent more time on election rallies, than handing the national Covid strategy. As the country breaks the world record of daily new cases of Coronavirus patients, and a soaring and still under-reported death tool, experts warn that the worst is yet to come. A reckless election campaign in five populous states had just wound up.

India is in the grips of an avoidable catastrophe. In a country that prides itself as the pharmacy to the world, patients are gasping for breath and crematoriums are running out of place. While an unprecedented second wave of the Coronavirus pandemic had been building up, its Prime Minister, Narendra Modi indulged most of his time in a vindictive election campaign. His political strategist and home affairs minister Amit Shah, spent more time on election rallies, than handing the national Covid strategy. As the country breaks the world record of daily new cases of Coronavirus patients, and a soaring and still under-reported death tool, experts warn that the worst is yet to come. A reckless election campaign in five populous states had just wound up.

This should not have happened this way. In February, India came tantalisingly close to beating the virus. The daily new cases dropped to 11,000. As of March, it was still 13,000. It felt like that the country was on its way - if not it had already been there- to flatten the curve. Populist Mr Modi declared a premature victory. His party, the Bharatiya Janata Party passed a resolution congratulating the prime minister of defeating the pandemic. Mr Modi, a divisive Hindu nationalist, announced elections for five opposition-held states and unleashed a vituperative campaign against, Mamata Banerjee, the chief minister of West Bengal and a formidable nemesis.

This should not have happened this way. In February, India came tantalisingly close to beating the virus. The daily new cases dropped to 11,000. As of March, it was still 13,000. It felt like that the country was on its way - if not it had already been there- to flatten the curve. Populist Mr Modi declared a premature victory. His party, the Bharatiya Janata Party passed a resolution congratulating the prime minister of defeating the pandemic. Mr Modi, a divisive Hindu nationalist, announced elections for five opposition-held states and unleashed a vituperative campaign against, Mamata Banerjee, the chief minister of West Bengal and a formidable nemesis.

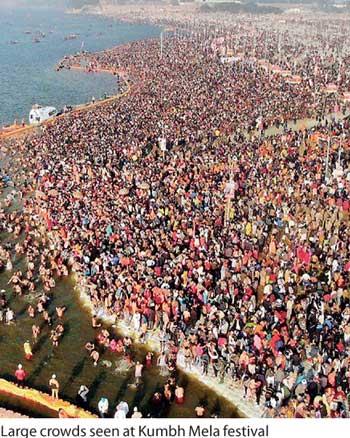

As experts warned about the spread of new dangerous double mutant, Mr Modi threw crumbs to his Hindutva votebase and granted permission to Kumbh Mela, a Hindu religious festival, where a mass gathering of millions of devotees take a ritualistic bath in the river Yamuna. The event is now dubbed a ‘super spreader’.

Images beaming from India is exceedingly distressing, and yet mostly middle-class centric coverage may be under-reporting the real tragedy of its poor. However, At least in one count, India’s mismanagement under its populist strongman leadership fits a universal pattern. Populist strongmen had shown almost criminal incompetence and indifference in their nations’ fight against the Coronavirus pandemic. In the United States, Donald Trump reigned over the death of 500,000 Americans, while, undercutting his own administration and state-level measures introduced by Democratic governors. In Brazil, another strongman Jair Bolsenoro had presided over 400,000 deaths, while the health system of South America’s largest economy has collapsed. Both he and Mr Trump pooh-poohed of wearing masks. Elsewhere, less known strongman like Tanzania’s John Magufuli has died suspiciously after Covid rumours.When he was alive, he said the virus had been eradicated by three days of prayers.

If you need an example too personal, look no further than our own. Sri Lanka is now in the heart of a dangerous third wave of Coronavirus, which has already dwarfed its previous upturn. The seven-day average ending May 2 is 1,481. However, the country’s covid chart since April 17 is a straight vertical line, mimicking the Indian experience. There were 1,891 new cases on May 2, according to the Ministry of Health. That alone is more than the daily toll of the UK (1,671), a country three times Sri Lanka’s population, that had flattened the curve from 60,000 daily cases from January this year.

With even the modest numbers of new cases in international comparison, the Sri Lankan health system is already dangerously overburdened. Hospitals have run out of ICU beds, and trade unions report orders to scale down on random PCR tests. Labs are churning out PCR reports 3-4 days behind the schedule. Medical officials warn about a looming oxygen shortage. The country’s vaccination effort had run out of stocks as half a million await for the second dose of AstraZeneca vaccine. An estimated eight per cent of those who took a PCR test has tested positive, rising from just three per cent three weeks back. At the current rate, unless expanded rapidly, PCR testing capacity would fail to keep up with the rising number of cases. Sri Lanka is at the foothill of a dangerous climb.

This should not have happened this way either. Like in India, Sri Lanka had brought the virus under control. In March, new cases were in 300 and dropped to 200 in the first week of April. Those lean times should have been used to crush the virus. Instead, the politico-military officials who run the coronavirus strategy thought that was time for a premature display of the government’s success. In much of Europe, the governments imposed a lockdown ahead of Christmas to preempt the mass gatherings. In Sri Lanka, all precautions were thrown into the air. The country celebrated Avrudu in grandeur and plans were afloat for the May Day celebrations though the rapid spiral of the virus put those plans to rest.

Sri Lanka’s current plight, just like in India is a result of its own government’s choices. Like Narendra Modi, Gotabaya Rajapaksa is a populist strongman. They, though elected by popular vote, have contributed to the erosion of norms, values and institutions of those constitutional democracies that enabled their coming to power.

Paradoxically though, their mismanagement of Covid is also in contrast to the performance of another sort of strongman regimes. Pro-growth authoritarian regimes, whose main call for legitimacy is the effective delivery of economic growth and services to their population. Some of these countries, such as China and Vietnam are the world’s most successful covid beaters.

Why would some kind of authoritarianism deliver while the other flounder and plunder?

First, against the conventional wisdom, pro-growth authoritarian regimes like China and Vietnam, and less talked about example such as Singapore, which covers its ugly side with skillful branding, are also prolific institutional builders of their own kind. China’s and Vietnam’s Communist parties are some of the most efficient bureaucracies in the world. Messrs Modi and Rajapaksa, aspire to have a degree of performance legitimacy. But, rather than building institutions and bureaucracies, they have dismantled them. Their dislike of intelligentsia with a different view and preference to like-minded cronies have undermined the institutions of the state. Mr Rajapaksa who said he could have defeated Coronovirus if it were war, has still appointed a military official to head the Covid task force. Where the structures of the state are blunted, so would their contribution to policy. It might help to erase certain doubts if the Health officials tell how much influence they have over Sri Lanka’s covid strategy and why they fail to take appropriate action to mitigate the effects of dangerous new mutants.

Second, pro-growth authoritarians rely first and foremost on performance-based legitimacy, though they might, from time to time, whip up nationalism as a convenient force multiplier. That also means they have little reason for intentionally divisive tactics pitting communities against each other. Whereas the populist strongmen have to pander their audiences, hence self-defeatist policies like Muslim bashing and compulsory cremation. If that proactiveness is better used to secure an early supply of vaccines, Sri Lanka would have been in a better position.

The third is the personalities themselves. In contrast to the popular myth of nepotism and favouritism, in most pro-growth authoritarian states, such as China and Singapore, getting to the top is a highly competitive business, which takes a whole lifetime of policymakers. The decades-long training also instil a good dose of common sense, that prevents leaders from indulging self-defeatist pie in the sky policies- , though not related to this specific topic- like the ban on chemical fertilizer. Those leaders are single-minded, go-getters and not the wannabes their populist counterparts are.

You can now see the vast difference in their performance in distressing detail.

Follow @RangaJayasuriya on Twitter

29 Nov 2024 19 minute ago

29 Nov 2024 44 minute ago

29 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

29 Nov 2024 4 hours ago