09 Dec 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

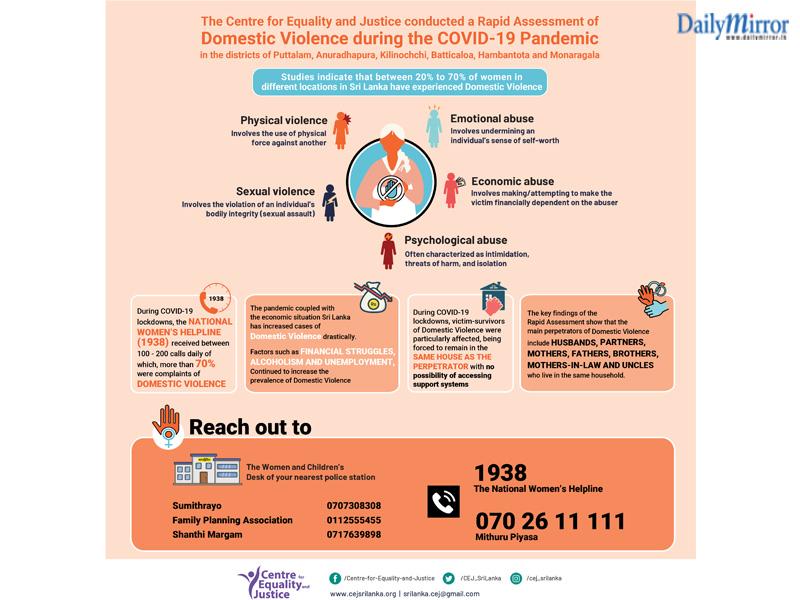

The pandemic and the accompanying lockdowns that took place in Sri Lanka in 2020 - 2021, and the worsening economic crisis that followed has only made worse another crisis that has been prevalent in the country for decades; a domestic violence (DV) crisis across the island, where, primarily women, are victims of abuse at the hands of an intimate partner. The pandemic brought about a notable increase in the number of complaints of DV, and as economic deprivation heightens, in all likelihood such cases of abuse will rise further.

In this backdrop, there is an urgent need to do more to combat DV, and provide assistance to victims. Some may argue that the economic crisis results in less resources being available to be allocated for this purpose, but the importance of prioritising the protection of vulnerable women must not be understated. Even with a minimum inflow of new resources, existing systems can be made more efficient, which would go a long way in assisting victims or potential victims of DV. The needs of victims of DV, which have long been put on the backburner of priorities, must be brought to the forefront, especially as the urgency of their needs increase.

Primarily, what needs to be done is twofold; on the one hand, the level of support given to victims of DV must be improved and on the other, steps need to be taken to reduce the incidence of DV, by identifying root causes and nipping them in the bud.

When responding to a complaint by a victim of DV, the urgency of the matter must be understood; a delay of a few hours, let alone a few days can render the whole process ineffective. First responders to a complaint of DV must be taught to value the gravity of the circumstances they have been entrusted to deal with, and the sensitivity they must show to the situation of a vulnerable victim. While training is often cited as a solution, occasional workshops for and seminars alone cannot bring about this change. Designated officers with an in depth understanding of what is required of them must be assigned to roles dealing with victims of DV.

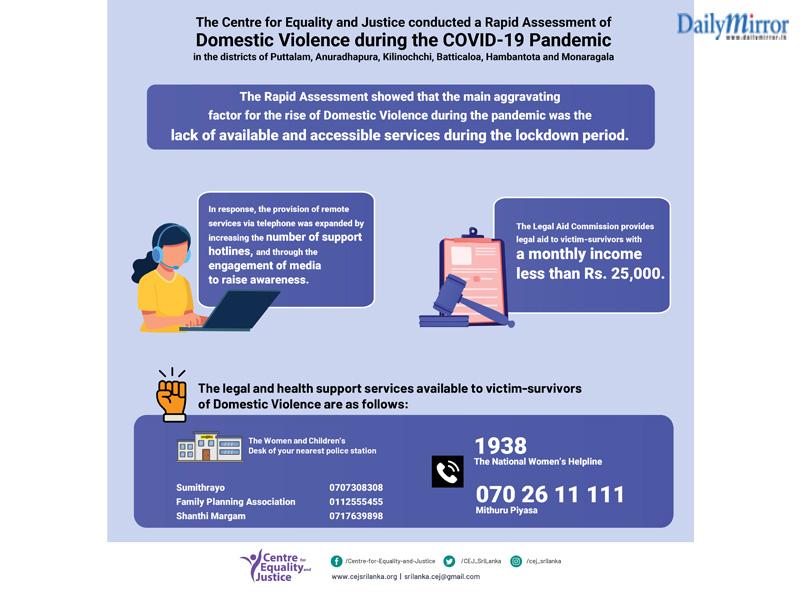

Often, approaching the criminal justice system will be intimidating for a victim of DV, and doing so may come with its own set of risks. Thus, victims are more likely to access the system if they have trust in its efficacy. A victim of DV may also be deterred from seeking help if the system requires many administrative steps, and going from place to place to access different services. Dysfunctional systems can result in more harm to the victim, especially if the lack of quick assistance means she has to go back home to her abuser. Streamlining the process, and bringing all these services to one access point will make the system more welcoming to a victim who is afraid to access it.

There are several steps that can be put into place immediately to help victims of DV, many that only require the revamping of existing services. For instance, hotlines to seek help can go a long way to help victims in immediate need, but they are sometimes found to be unresponsive. Media campaigns that teach the public when to step in and assist a victim can also be effective - hand signals like the ‘Signal for Help’ (repeatedly folding fingers up and down over the thumb folded into the palm) can be effective if they are known to the victim and widely recognized by the public.

In terms of nipping DV in the bud and reducing the rates at which it occurs, there are two areas that require focus; one is education, and the other, addressing the factors and frustrations that lead to aggressive behaviour. Education must be both aimed at eliminating gender stereotypes and empowering girls from a young age to express and defend their agency. The stereotypes and gender roles that eventually lead to DV are so deeply rooted that a complete overhaul of perspective will be needed to change it. A few lessons in the school curriculum alone may not have the desired results, the type of education that is needed for this must also come from the home, religious institutions, the media and in the general conduct of adults that children look up to.

In terms of the causes of the aggressive behaviour, experts in the field speak of two primary problems; one is that rates of child abuse and corporal punishment in the country are high, and so from a young age, violence is identified as a legitimate way of expressing anger or annoyance. The other is that many men who abuse are frustrated by their financial circumstances or various addictions and even if they are taught to recognize that their behaviour is wrong, their circumstances make it a challenge to break out of the cycle of abuse. While psycho-social assistance is recognized as important for victims of DV, these other groups too must be given similar assistance to break the cycle.

These changes don’t require mass inputs of funding to be effective. What is most lacking is the political will to actually bring about change. The ‘Aragalaya’ saw millions of Sri Lankans out on the streets demanding change, spurred on by concerns with costs of living. It is important that the suffering of the most vulnerable in society, including victims of DV who often lack a voice to defend themselves, is not forgotten in these calls. If this is done, significant change is possible.

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago