11 Dec 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Restrictions on movements and lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic made women, girls and children susceptible to a more severe crisis, namely domestic violence. While lockdowns forced families to remain indoors, loss of employment, stress caused by debilitating economic conditions, alcohol and drug abuse aggravated sexual violence as well. The Centre for Equality and Justice (CEJ) together with their district partners conducted a rapid assessment on domestic violence and related services in the Puttalam, Anuradhapura, Kilinochchi, Batticaloa, Hambantota and Monaragala districts. Key informants of the assessment included front-line government officers, including the Sri Lanka Police, Women Development Officers, Counselling Officers, Grama Niladharis, public health midwives, officers of the NCPA, health sector professionals including medical doctors and psychiatrists, nurses and matrons, local women’s and civil society organisations providing services to victim-survivors of violence.

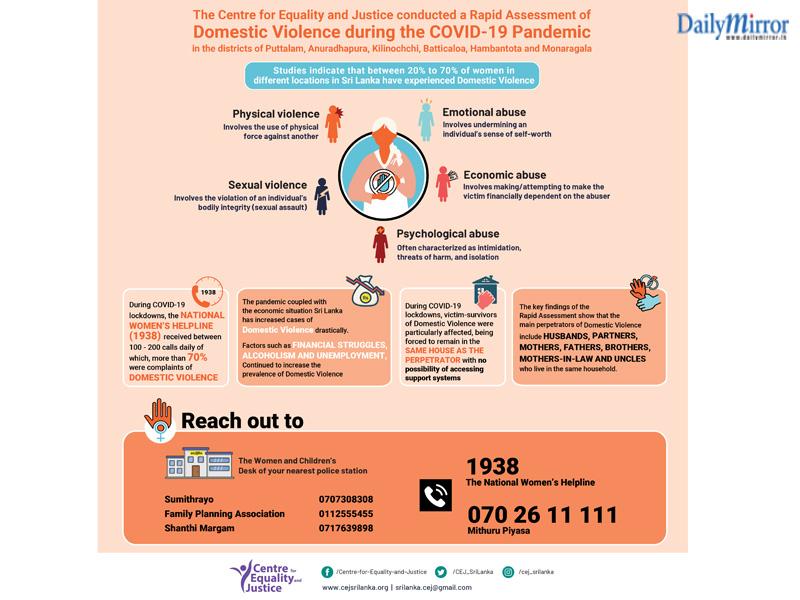

The Prevention of Domestic Violence Act No. 34 of 2005 (PDVA) broadly defines domestic violence as ‘specified offences contained in the Penal Code to include sexual abuse and exploitation, sexual harassment, physical abuse, assault, use of criminal force, incest, rape, causing miscarriage, wrongful and unlawful confinement, attempted murder as well as extortion and criminal intimidation and any attempt to commit one or more of such offences’. The definition also includes emotional abuse – a pattern of cruel, inhuman, degrading or humiliating conduct of a serious nature directed towards an aggrieved person, committed or caused by a relevant person within the environment of the house or outside and arising from a personal relationship between the victim-survivor and the perpetrator.

The most prevalent form of domestic violence is intimate partner violence against women. The Women’s Well-being Survey 2019 revealed that women in Sri Lanka are twice as likely to have experienced physical violence by a partner (17.4%) than by a non-partner (7.2%) and found that 24.9% of women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence. Victim-survivors of violence, particularly women and girls have been among the population groups most severely affected by the restrictions on movement and lockdowns as a majority had to remain in the same house as the perpetrator with no possibility of accessing support systems or services. With hotlines receiving more complaints of domestic violence during the lockdown period, media reports also indicated higher numbers of victims of domestic violence being admitted to hospitals.

The findings of the CEJ report indicated an increase in the number of incidents of domestic violence across all districts. But there were no formal complaints since women were unable to reach service providers due to travel restrictions and lack of transport services. In some instances, women would report directly to the Police. Most incidents were reported by neighbours, relatives or community leaders informing the grama Niladhari, Police hotline 119, 1938 hotline, WDOs, local women’s organisations, CSOs or by the perpetrators themselves out of fear that if the victim were to die, their children would be left without any parent to care for them. Perpetrators of domestic violence include husbands, partners, mothers, fathers, brothers, step-fathers and grandfathers, brothers-in-law, fathers-in-law and mothers-in-law who live in the same household.

All incidents highlight the stigma attached to reporting incidents or experiences of domestic violence which prevents women from seeking assistance at an early stage. As a result, many women denied that they experienced any sort of violence when officials visited them at home following an incident. Women in Anuradhapura, Puttalam and Monaragala were extremely reluctant to report domestic violence primarily due to fear of social shame and stigma. On the other hand, women were cut off from their support structures which included talking to friends or relatives, and going to social or religious events mainly due to restrictions. But some interviews highlighted how the husband forbade the woman from maintaining any contact with friends or relatives in order to isolate her.

As a result, emotional violence was reported as the most prevalent form of violence during the pandemic owing to many reasons. Women, although overwhelmed and exhausted with work had to carry out all household work, take care of children as well as meet all sexual demands of their husbands. All districts reported that women were forced to have sexual relations with their spouses, partners and often, contraception was not available. Reports of underage pregnancies and incidents where husbands or partners have urged women to undergo abortions too were reported.

Women who couldn’t bear children were belittled and men also suspected women to be having extramarital affairs. Key informants in Kilinochchi highlighted that many women attempted suicide, mostly due to partners having extra-marital affairs or having other intimate partners. Some victim-survivors even attempted to take their own lives as they were unable to bear the violence.

Loss of employment and income made people live with anxiety and stress while a spike in alcohol and drug abuse too was observed during the pandemic. Husbands who were addicted to alcohol and/or drugs would sell household items or children’s jewellery and this led to disputes and subsequent violence. Men, women and children needed counselling and psychosocial support to help deal with stress, anxiety and depression but with no coping mechanism to help process their feelings, many resorted to violence.

Doctors in Anuradhapura, for example, witnessed a spike in women seeking treatment for high blood pressure and these incidents were believed to be a possible result of experiencing domestic violence. Some women were unable to openly express the cause for their physical and psychological problems, even though the root cause was domestic violence.

The issue of neglect made children more vulnerable to violence and this was often inflicted by the father, mother, stepfather, uncle, and/or neighbours. In Hambantota for example, household expenses increased exponentially since the entire family was forced to remain at home. Since many parents were unable to cope with this, they would react in anger toward their children. Incidents of a child being raped by a stepfather while the mother was in quarantine, and a child raped by the father as a means of taking revenge on the mother who migrated overseas for work were reported. Underage marriage, cohabitation and sexual relationships with a minor were other incidents that were reported during the height of the pandemic.

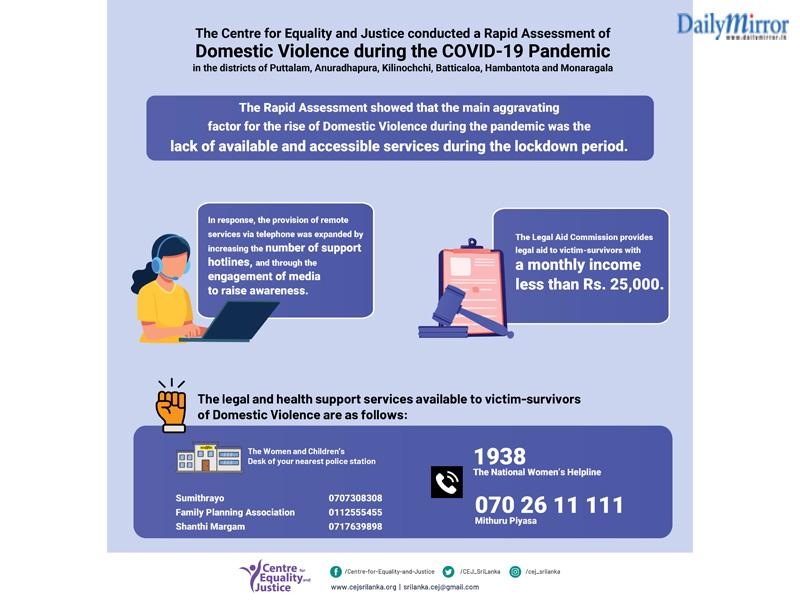

But even though women relied on government support, it didn’t reach out to everyone in need. In places like Kilinochchi, government offices were closed even before the pandemic hit. In Monaragala, there have been no services offered by the Divisional Secretariat due to the closure of offices and limited staff. On the other hand, women didn’t have money to recharge their phones to report incidents. According to a counsellor in Hambantota, the biggest challenge was to reach out to women who didn’t have a mobile phone. The aggravating factor for the increase in domestic violence was due to the lack of available and accessible services during the lockdown period. Counsellors too were challenged due to the lack of transport and were unable to do follow-up treatments or attend to urgent cases.

Even though the Police would have been the go-to option for women who were battered by these incidents, key informants described how the Police discouraged women from reporting incidents of domestic violence. Officers were attempting to resolve conflicts informally and advising women to return to the perpetrator. The Police were preoccupied with addressing curfew and quarantine violations and with hospitals reaching maximum capacity, people were discouraged from seeking support or medical attention respectively, unless critical.

Another significant barrier in offering them support was the lack of safe-spaces to house victim-survivors in Puttalam, Kilinochchi, Hambantota and Monaragala. A counsellor emphasised that the lack of safe homes to shelter women drove them to resort to suicide as the last course of action. The main course of action by women’s organisations and CSOs was to create volunteer groups and links that would provide temporary shelter to women in need. Another option was directing women affected by violence to seek shelter at their relatives’ houses. However, women have shown reluctance to seek shelter within the Police station owing to fear of further violence being committed against them.

However, after March 2020 many institutions increased the number of hotlines and their staffing capacity to ensure 24-hour access to hotlines. In all six districts, both government officials and women’s organisations were able to provide assistance over the phone. Women’s groups formed a link between victim-survivors and the Police or hospitals for example, as they were more comfortable reporting their incidents to these groups that had a women development officer. In places such as Kilinochchi, CSOs reported language barriers when communicating as most government officials spoke Sinhala language and were therefore unable to communicate with the predominantly Tamil-speaking population and this situation was made worse when the only means of access was via telephone.

Referral systems for example had provided some relief in certain districts where the government officers would collectively respond to reported cases of domestic violence. Coordinated responses between the Grama Niladhari, women development officers, police, counselling officers and hospitals too had reflected benefits in districts such as Puttalam, Anuradhapura, and Batticaloa. However, informants had expressed dissatisfaction regarding the legal response to domestic violence. Certain courts restricted functions to urgent matters only and these mainly included bail hearings. Domestic violence or maintenance cases were not considered urgent. If the police and local women’s groups had a good rapport, the police would provide a number to reach out to during an emergency. However, while some districts had facilities to provide shelter for victim-survivors, few other districts faced difficulties due to the unavailability of shelters. Women’s groups and civil society have also extended social support to families as means of easing the financial burden.

Several recommendations were suggested in terms of disaster response and management, justice, service and awareness. These include;

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago

22 Dec 2024 7 hours ago