29 Jul 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Piyumi Fonseka

Money matters in Sri Lankan elections. Despite constant public discussion about the massive costs of election campaigns in Sri Lanka, there is a lack of credible data on the actual costs, the sources of funds, and the consequences of campaign financing on governance aftermath the elections.

It is a famous secret that many shady deals are taking place in the desperate hunt of candidates for campaign cash. From rice packets and alcohol distribution to deposit slips of millions of rupees, money plays a key role in Sri Lankan elections. However, the unholy nexus between money and politics in Sri Lanka has not been the subject of continued public attention. Is this just because of the lack of credible data or is it also due to the lack of interest of the general public?

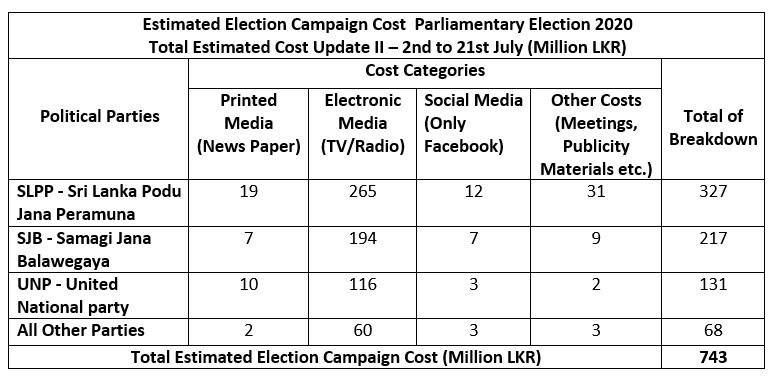

Below are the latest findings of campaign costs of political parties for upcoming general elections disclosed to Daily Mirror by the Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV).

It’s worth mentioning what we did not find; who funds these candidates and what their expectations are of the candidates in return for their money.

A key question, to date unanswered, is the degree to which political parties provide financial support to candidates.

Manjula Gajanayake, the National Coordinator of the CMEV claimed that financial support of parties is not provided to candidates according to Constitutions of relevant parties.

“The candidates who are more powerful with stronger and closer relationships with higher-ups of the political parties receive more money for their campaigns than other candidates. According to annual reports of the main political parties, only around 10% contributes to the total funds provided by the parties for their candidates,” he stated.

In addition to party funds, what are the other sources? CMEV’s National Coordinator stated that money laundering takes place in a larger scale during elections than in underworld activities. There are so many foreign funds also financed in elections.

The fairness of elections rely in part on the campaign finance framework. Unregulated campaign finances have led to an uneven playing field for candidates and also created a new risk of foreign and domestic interference in the elections and even in the governance after the elections.

Therefore, another question voters should raise is what the funders’ expectations are in return for their money. What do they deal to get back from the candidates when they possibly win and get a ticket to the parliament which is the supreme legislative body of Sri Lanka that alone possesses ultimate power over all other political bodies in the island?

Gajanayake’s answer to this question was that the general public will ultimately have to pay the price for such shady election deals. The only possible way for candidates to repay or return help they received from their ghost funders is through pleasing the funders with relief and aid. It may come as illegal tax relief, aid in importing and exporting goods and services of businesses owned by the funders or any other way of misusing political power.

The national legal framework of Sri Lankan Elections is based on the Constitution of Sri Lanka, the Registration of Electors Act, the Referendum Act, the Presidential Election Act, the Parliament Elections Act, the Provincial Council Elections Act, the Election Special Provisions Act and the Local Authorities Election Ordinance.

The national legal framework of Sri Lankan Elections is based on the Constitution of Sri Lanka, the Registration of Electors Act, the Referendum Act, the Presidential Election Act, the Parliament Elections Act, the Provincial Council Elections Act, the Election Special Provisions Act and the Local Authorities Election Ordinance.

In addition, the Election Commission has the authority to prohibit the use of any movable or immovable state property for the election campaigning of any political party, group or candidate.

The Parliament Elections Act prohibits vote buying both directly and indirectly, by himself or by another person on his behalf to give, lend, agree to give or lend or offer, promise any money or valuable consideration to or for any elector or to or for any person on behalf of any other person in order to induce any voter to vote or refrain from voting. Vote buying is also prohibited in the Presidential Election Act, the Provincial Council Elections Act and the Local Authorities Elections Ordinance.

However, there is no legal framework in the country to regulate campaign financing. The only practice is candidates submitting their assets declaration to the Election Commission. Despite that, such assets declarations have never been properly investigated or even published for the general public.

An election campaign finance law has the capability to put a cap on election expenses and would make it mandatory for candidates to reveal their campaign expenditure and sources of funds.Although election watchdogs such as People’s Action for Free and Fair Election (PAFFREL) and CMEV have been lobbying for the Election Campaign Finance Bill, the Bill is still stuck at Attorney General’s Department.

An election campaign finance law has the capability to put a cap on election expenses and would make it mandatory for candidates to reveal their campaign expenditure and sources of funds.Although election watchdogs such as People’s Action for Free and Fair Election (PAFFREL) and CMEV have been lobbying for the Election Campaign Finance Bill, the Bill is still stuck at Attorney General’s Department.

Gajanayakeof the CMEV said, “we wanted to get the election campaign finance law passed before this general election. But, it is still stuck at the AG’s Department. Unfortunately, with the existing law, there is no limit for private funding for election candidates. If we had passed the bill, it would have minimized or prevented the use of black money in election campaigns which is currently happening at large,” said.

He said a public discussion has to be created on the impact of unlimited and unregulated election campaign financing.

“During the Presidential Election held last year, we as the CMEV found out that Rs. 3796 million was spent by all 35 presidential candidates for their campaigns. It was a huge amount and the amount itself could have stirred a public concern. But, unfortunately, we did not notice any interest from the general public about the staggering amount of money that was spent.

He also said the voters have a right and also a responsibility to question candidates on their election campaign financing and even to go further and investigate the sources of campaign funds.

01 Jan 2025 12 minute ago

01 Jan 2025 40 minute ago

01 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

01 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

01 Jan 2025 5 hours ago