15 Sep 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Parliamentarians—so-called supreme legislators—wear white, the colour of peace and purity. But how many of them actually behave as such? In November 2018, Sri Lankans and the whole world witnessed one of the worst and most disgraceful breakdowns of discipline by lawmakers.

Parliamentarians—so-called supreme legislators—wear white, the colour of peace and purity. But how many of them actually behave as such? In November 2018, Sri Lankans and the whole world witnessed one of the worst and most disgraceful breakdowns of discipline by lawmakers.

A special committee was appointed to look into the unruly incidents – the first step any Sri Lankan government authority takes in order to investigate any wrongdoing. Needless to say that this is also the step that often leads to a dead end.

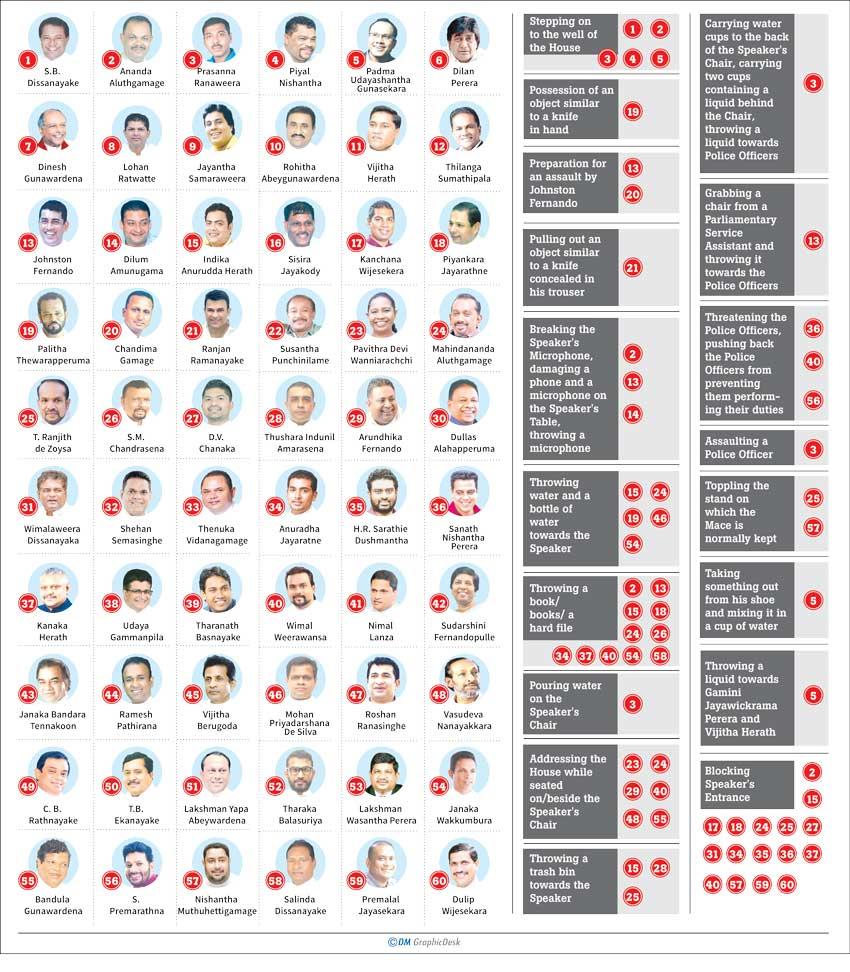

The special committee report, which recommended legal actions through the Supreme Court against a total number of 60 parliamentarians (55 = UPFA, 4 = UNP, and JVP = 1) for violating the Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, didn’t see its recommendations being implemented. The Daily Mirror obtained a copy of the report through an RTI application filed by the writer.

Has the report been thrown into the bin? Under whose pressure was the investigation put on hold? Did this committee end up being just another one that spent taxpayers’ money investigating the misconduct of lawmakers? Where is accountability?

What happened in November 2018?

On November 14, 2018, the day the first 1st Motion of No Confidence against Mahinda Rajapaksa was passed in Parliament, the unrest erupted when opposing lawmakers exchanged fisticuffs. MPs supporting Mahinda Rajapaksa rushed onto the chamber floor. They began brawling with lawmakers of the opposing party, and some began hurling water bottles and other objects at former Speaker Karu Jayasuriya.

The Speaker, on November 29 appointed the Special Committee to look into the matters pertaining to the unruly incidents that took place on the floor of the Parliament on November 14, 15, and 16. Chaired by Ananda Kumarasiri, the committee comprised Ranjith Madduma Bandara, former Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa, Chandrasiri Gajadeera, former JVP MP Bimal Rathnayake, and Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) Leader Mavai S. Senathirajah.

Emphasizing the importance of completing the investigation without any delay, the committee after six sittings with testimonies of hundreds of various parties including journalists who were present in Parliament completed its investigation report by January 2019 which was presented to the Speaker for further action.

What did the committee report reveal?

On the first day of the committee, former Speaker Chamal Rajapaksa along with Chandrasiri Gajadeera withdrew themselves from participating in the proceedings of the Committee. It must be noted that Chamal Rajapaksa is the eldest sibling of the Rajapaksa family.

After viewing all the video recordings, the Committee prepared a list indicating the names of Parliamentarians who created the unrest situation. According to the report’s findings, the parliamentarians have breached the Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act as well as Standing Orders and committed offences coming under the scope of Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, which is punishable under section 22 of the said Act.

Other MPs whose names (numbers) are not listed in the offences mentioned above, were found to have violated law and order in Parliament by gathering around the Speaker’s Chair and causing chaos.

Where did the report get stuck and why?

Senior Deputy Solicitor General Rohantha Abeysuriya, who was nominated by the Attorney General as per the request of the committee provided the necessary legal advice and guidance to the committee. A police investigation had already been initiated based on 17 complaints, the Welikada Police Station had received regarding the disturbing incidents that took place in Parliament. The Committee multiple times stressed the need to conduct police investigations into such complaints independently and without interference.

“Don’t know what happened after we handed over the inquiry to CID”: SDIG Nandana Munasighe

When the Daily Mirror contacted Senior Deputy Inspector General Munasighe, he said that with the purpose of further expediting the independent investigation, initially handled by the police, was handed over to the Criminal Investigation Department.

“We handed over our police investigation to the CID. We don’t know what happened to it after that. But, I remember there was a discussion among the attendees of the committee that this incident and whatever the punishments recommended for the responsible parliamentarians should not go beyond the walls of Parliament,” Munasinghe said.

“There was pressure after RW became the PM to drop the charges against the involved parliamentarians”: Committee Member Forme JVP MP Bimal Rathnayake

The Daily Mirror also spoke to former JVP MP MP Bimal Rathnayake who was one of the committee members to find out if he is aware of what really happened to the report they worked on for over a month, spending taxpayers’ money.

According to what he said, when previous Speaker Karu Jayasuriya was in office, Rathnayake had brought up the issue in Parliament more than four times after the committee report was submitted to Parliament. However, he has received no clear response from the government party.

“It is very obvious that once Ranil Wickremesinghe took over duties as prime minister, he put pressure on the Speaker and other relevant authorities to drop the charges against the involved parliamentarians,” he claimed.

A few months after the release of the committee report, MP Kanaka Herath—named as one of the MPs who broke the law during these events—was appointed to the Panel of Chairs of Parliament. Rathnayake said he raised objections to the Speaker and questioned him about Herath’s appointment, but again he got no proper response.

It is ironic that an individual who has been found to have broken the Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, the Standing Orders, and the Code of Conduct for Members of Parliament has been nominated to such a high position.

According to Parliament Standing Order 140, the Speaker nominates, a Panel of Chairs to act as temporary Chair of Committees when requested by the Deputy Speaker or in the absence of the Deputy Speaker. Anything which may be done by the Deputy Speaker may also be done by a temporary Chair when presiding in place of the Deputy Speaker.

Who paid to replace damaged public property?

The damaged properties, including audio equipment and stainless steel bars in the Chamber, were replaced soon after the incidents in order to continue Parliamentary proceedings in a proper manner. According to the committee report, the initial valuation report sent by the Chief Valuer stated the value of the damage was just Rs.175, 000.00, whereas the replacement cost of the audio equipment was Rs.299.165.20 as per the estimate given by the manufacturer’s agent, and the replacement cost of the stainless steel bars in the chamber was Rs. 29,670.00 according to the estimate of the government factory.

Underscoring the significance of the accuracy of the valuation report, Senior Deputy Solicitor General Abeysuriya stated during the Committee session that the accuracy of the valuation report would be essential since, under the Public Property Act, the fine will be three times the value of the damaged property.

Subsequently, the cost assessment to restore all the equipment and appliances damaged inside the house was finalised as Rs. 325,000.00 without taxes and other charges imposed on goods and services by the government.

How the unruly MPs could be punished by law

Attorney General’s representative SDSG N. R. Abeysuriya, explaining the legal position regarding these incidents stated that even though Parliament (Powers & Privileges) Act is to ensure freedom of speech and debate in Parliament for MPs, it certainly does not provide immunity for any criminal act. He was of the view that there could be no legal barrier to taking legal action under the General Law of the country against the MPs who had committed criminal acts in the House and also damaged Parliament property.

However, if steps were taken only under the Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, he underlined that there could be complications. Hence he recommended that action should also be taken under the Penal Code and Public Property Act if sufficient material were available against the MP to constitute an offence punishable under the law. He further stated that taking steps under the Criminal Law in respect of these offences would have a more deterrent and preventive effect.

SDSG Abeysuriya explained before the Committee that, as clearly stated in Sub Section 2 of Section 31 of the Parliament (Powers and Privileges) Act, where any act which constitutes an offence under this Act also constitutes an offence under any other law, no section of this Act shall be interpreted as preventing or restricting action of prosecuting or trying a person who is guilty of such act.

He also explained before the Committee that, although it may take some time for imposing punishment regarding offences stated in the Act, it is by taking action under civil laws or under the provisions of the Civil Procedure Code that deterrent punishments, which may have a greater impact on the offender, can be imposed.

Fights and brawls in Parliament are not something new. According to the committee, several parliamentarians who took part in the November 2018 chain of events have taken part in grave indiscipline conduct in Parliament on previous occasions as well and disciplinary action has been taken by Parliament against them. Evidently, standard disciplinary actions – temporary suspension of attendance ranging from one week to three weeks – haven’t really been effective.

Research has shown that increased information about MPs and their misconduct may lead to greater accountability by aligning the behaviour of MPs, who want to be elected, with the expectations of voters who will electorally punish misconduct. There is, however, mixed evidence for whether voters do punish MPs for misconduct at election times. The regulation of parliamentary behaviour and ethical standards is an essential element to secure public trust in the efficacy, transparency, and equity of democratic systems, as well as fostering a culture of public service. The primary goal of the Aragayala– ousting former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa – has been achieved. However, it seems unlikely that Sri Lanka’s hope of seeing an orderly, well-behaved parliament is growing more distant by the day.

25 Dec 2024 9 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 9 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 9 hours ago