Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Small scale fishermen in Kalpitiya seen fishing in the lagoon following the ban on illegal bottom trawling

For Kingsley Croos, a fisherman from Palgahathurai, one of 14 islands that shapes the Kalpitiya peninsula, illegal bottom trawling has been a curse that wreaked havoc in his life. As populations of shrimp, sea crab and other fish species found along the sensitive Puttalam estuary declined, Croos and fellow fishermen knew that their livelihoods would be threatened forever. It was after January 2021, that these fishermen breathed a sigh of relief with the cessation of illegal trawl net fishing by multi-day fishing boats.

For Kingsley Croos, a fisherman from Palgahathurai, one of 14 islands that shapes the Kalpitiya peninsula, illegal bottom trawling has been a curse that wreaked havoc in his life. As populations of shrimp, sea crab and other fish species found along the sensitive Puttalam estuary declined, Croos and fellow fishermen knew that their livelihoods would be threatened forever. It was after January 2021, that these fishermen breathed a sigh of relief with the cessation of illegal trawl net fishing by multi-day fishing boats.

Productive ecosystem

Productive ecosystem

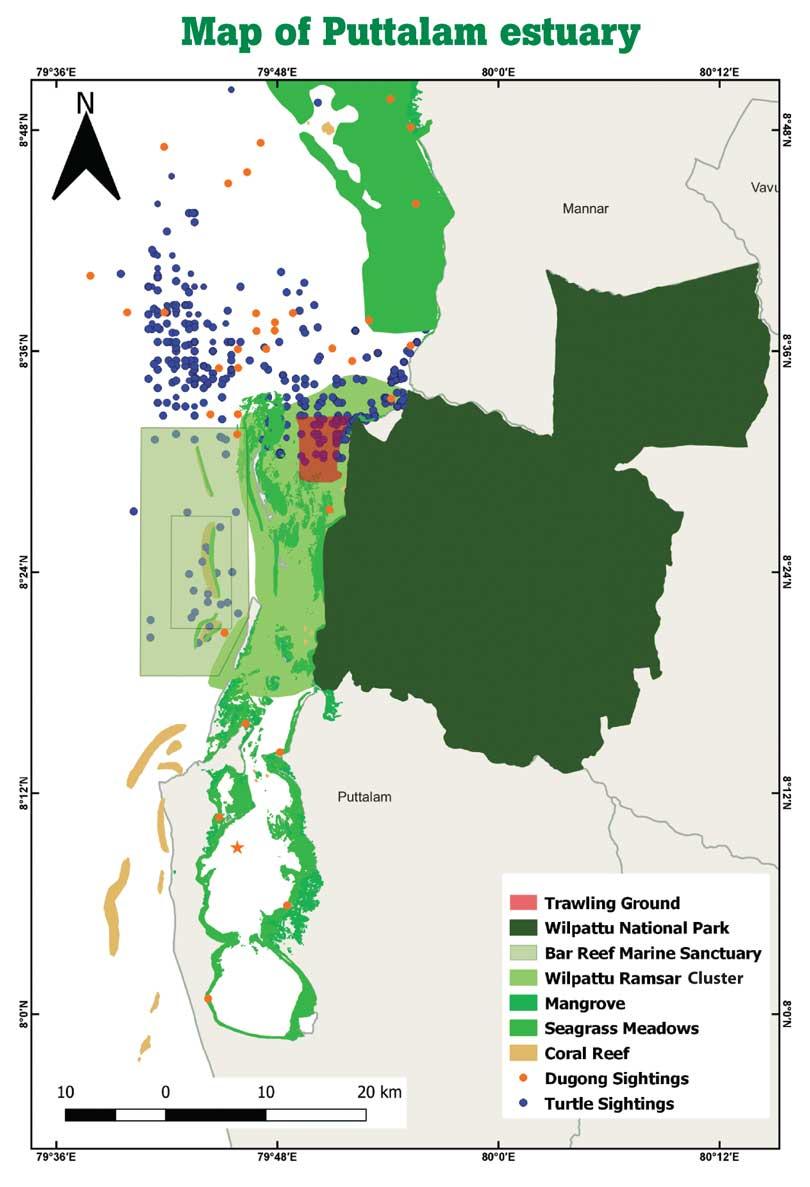

In a Writ Application (CA/W/463/20) filed by the Environmental Foundation Limited (EFL), an Organization dedicated to the protection and conservation of the environment and has been involved in public interest litigation for over 35 years, states that the Puttalam estuary is one of the most productive and dynamic water bodies in the North Western Coast of Sri Lanka. The estuarine complex consists of the Dutch Bay and Portugal Bay. The Application was filed with the support of advocacy groups such as Pelagikos to bring about a ban on illegal bottom trawling along the Puttalam estuary by multi-day boats. The Puttalam estuary is a highly productive ecosystem sustaining a wealth of resources including economically valuable fish and shellfish species, sea grasses and mangrove habitats. The Petitioner underscored that the estuary also has a significant conservation value since the Bar Reef Marine Sanctuary and Wilpattu Ramsar Cluster are located towards it north.

It makes sense that there are more prawns and other types of fish throughout the estuary after the illegal trawl activities stopped at the mouth of the estuary. The trawlers were harvesting the adults, spawning stock of the green tiger prawn population (flower shrimp/ Penaeus semisiculatus) at the mouth of the estuary

- Dr. Steve Creech, Fisheries Expert

With destructive fishing methods such as bottom trawling these species find new habitats. If this practice (bottom trawling) doesn’t stop we will have to beg on the streets. There’s nothing in the lagoon as of now

With destructive fishing methods such as bottom trawling these species find new habitats. If this practice (bottom trawling) doesn’t stop we will have to beg on the streets. There’s nothing in the lagoon as of now

- Kingsley Croos Treasurer of

St. Velankanni Fisheries Cooperative

With more bottom trawling practices taking place we realised that populations of flower shrimps were dwindling. But when a ban was imposed on bottom trawling for around six months, this species of shrimps emerged once again. When the ban was lifted, these shrimps vanished

With more bottom trawling practices taking place we realised that populations of flower shrimps were dwindling. But when a ban was imposed on bottom trawling for around six months, this species of shrimps emerged once again. When the ban was lifted, these shrimps vanished

- W. Francis Fernando, former President

Fisheries Cooperative Society, Janasaviyapura

Most small scale fishermen made a living by catching shrimps. There were around 200-500 boats. But eventually none of these boats went to sea because with bottom trawling almost all of them lost their jobs

Most small scale fishermen made a living by catching shrimps. There were around 200-500 boats. But eventually none of these boats went to sea because with bottom trawling almost all of them lost their jobs

- Saman Nishantha, President

Thoradiya Fisheries Cooperative

Prospective hunting ground

Bottom trawling is a destructive method of fishing which involves the use of a large net with heavy weights, which is dragged across the bed of the water body. During our visit to meet with the fishermen in the mainland and surrounding islands in the Kalpitiya peninsula, the Daily Mirror learned that the biggest trawling ground in Kalpitiya spans from the island of Karativumunai to K Point. Local fishermen told this newspaper that a large sea grass bed at the bottom of the estuary provides a potential breeding ground for most of its aquatic species. “But illegal bottom trawling bulldozes the estuary bed causing irreversible damage, catching endangered species, depleting fish stocks and plant life among other consequences,” they added.

Legal implications

Even though the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) imposed a ban on illegal bottom trawling in 2017 and the amendment was incorporated in the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act No. 2 of 1996, such destructive fishing practices continued in broad daylight. Small scale fishermen in Kalpitiya were particularly affected when around 23 multi-day boats started using illegal trawl nets to catch fish in abundance; thereby eating into the opportunities for small scale fishermen that otherwise would help them thrive.

According to Section 6 (1) of the aforementioned Act, an interested party should firstly acquire a licence issued by the Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources to engage in any of the prescribed fishing operations in Sri Lankan waters.

Regulation 3 of the Fishing Operations Regulations of 1996 published under dear Gazette Extraordinary bearing number 948/25 dated November 7, 1996 states that ‘No person shall engage in, or cause any other person to engage in any fishing operation specified in Part I of Schedule hereto, in the sea, estuaries or coastal lagoons of Sri Lanka except under authority of a license issued under these regulations..’

Trawling activities are restricted in inland waters as defined by the Inland Fisheries Management Regulations of 1996 which includes any public river, lake, estuary, lagoon, stream, tank and any other public area of fresh or brackish water in Sri Lanka. It further states that licences won’t be issued for certain types of fishing gear or boats. These include ‘any surrounding or towing net such as madel, purse seine and trawl net and any mechanized boat. This effectively means that mechanised trawlers won’t be able to obtain licences for fishing activities in inland waters.

Similarly, illegal bottom trawling is contrary to the principles and provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Sri Lanka became a signatory to the UNCLOS on December 10, 1982 and ratified the Convention on July 19, 1994. UNCLOS promotes the conservation, protection and preservation of the living resources in the high seas, in estuaries and marine environments.

Interventions and a landmark judgment

“Various researchers and consultants have been saying that bottom trawling in the Puttalam estuary (comprising Portugal Bay, Dutch Bay and Puttalam Lagoon) is detrimental to the estuary’s ecology and fisheries, but no one was taking any practical steps to stop it,” said Dr. Steve Creech, fisheries expert and Director at Pelagikos (Pvt) Ltd. “This is why we took practical steps with the support of EFL. It makes sense that there are more prawns and other types of fish throughout the estuary after the illegal trawl activities stopped at the mouth of the estuary. The trawlers were harvesting the adults, spawning stock of the green tiger prawn population (flower shrimp/ Penaeus semisiculatus) at the mouth of the estuary, thereby reducing recruitment to the stock (and juveniles / adults) throughout the estuary - depriving fishermen of the opportunity to harvest green tigers elsewhere in the estuary,” said Dr. Creech.

He further said that boats operating illegal trawl nets also indiscriminately harvested many other kinds of fish, crustacean (crab and prawn) and mollusc (squid, cuttlefish) species, almost all as juveniles. “Now that this indiscriminate harvest of many other kinds of fish, crustaceans and mollusc juveniles has stopped, two things would have happened. The juveniles of commercially important species have an opportunity to grow to adult size, which creates new or better fisheries for these species for small scale fishermen throughout the estuary. Juveniles from species that are not commercially important will be more abundant and will reach adulthood and reproduce in greater numbers,” he said.

Dr. Creech further said that non-commercially important species - known as forage fish - most likely serve a key ecological function by being consumed by commercially important species. “All in all the cessation of illegal bottom trawl net operations by multi-day boats in the Puttalam estuary is likely to have had a dual impact - directly enabling small scale fishermen to catch green tiger prawns using bottom-set prawn nets and indirectly by boasting the availability of forage fish. This in turn drives in and increases in abundance larger and commercially important fish in the Puttalam estuary; such as silver pomfret, sea bass, freshwaters eels - all of which fishermen have reported catching in great numbers since the illegal trawl net fishing stopped in January 2021,” he said.

A matter to rejoice

For most fishermen in Kalpitiya, the ban on bottom trawling is a victory and a blessing. Apart from fishermen in the mainland, fishermen in Palgahathurai experienced the biggest impact from bottom trawling. Their fishing ground was just 2-3 km from the shore, but with the emergence of bottom trawling they had to explore new depths to engage in their only profession through which they have survived since childhood. Even though Palgahathurai is a mainland, the only means of access to this place is by boat.

“We still can’t find sinnakkali (sea crabs, popularly known as Kakkutto) but we have observed that shrimps are once again returning to their habitats,” said Croos who is also the Treasurer of the St. Velankanni Fisheries Cooperative. Having been a fishermen since childhood, Croos explained how he observed the reduction of marine species with the emergence of bottom trawling. “With destructive fishing methods such as bottom trawling these species find new habitats. If this practice (bottom trawling) doesn’t stop we will have to beg on the streets. There’s nothing in the lagoon as of now. Back in the day, there was bottom trawling, but there was fish in abundance. But with continuous fishing the resources in the estuary have depleted,” he explained.

But over the past three years, Croos rejoices the fact that he doesn’t have to go further away to find his daily catch. “I can find shrimps around 2-3km from the shore. Over the past few days we had a good harvest of shrimps worth around Rs. 45,000-50,000,” he chuckled.

He further criticised how boats have been mechanised to further venture into the sea. “Back then, the boats didn’t have the capacity to go into the deep sea. But today the boats have been designed to go to any length of the lagoon. On the other hand, some fishermen engage in what is known as light diving where they would take a bright light and illuminate the underwater environment to find potential habitats. This is more unsustainable than bottom trawling and it is being done at night. As a result most aquatic species setup their habitats elsewhere,” he added.

Croos further said that with bottom trawling, if the fishermen catch around one kilo of prawns around nine kilos of bycatch can also be found in the net. “Those engaged in bottom trawling could very well engage in other livelihoods. The owners are influential people. If the ban continues small scale fishermen don’t have to go further into the deep sea or lagoon to find their catch for the day. Therefore we urge the government to be fair on us,” he added.

Apart from Palgahathurai, fishermen in the neighbouring islands such as Karativumunai and Baththalangunduwa also echoed similar sentiments.

“I believe that most issues faced by fishermen have been resolved with the ban on bottom trawling, said W. Francis Fernando, former President of the Fisheries Cooperative Society in Janasaviyapura, a remote area in mainland Kalpitiya. “Trawling (as is popularly termed) existed even when we were small. With more bottom trawling practices taking place we realised that populations of flower shrimps were dwindling. But when a ban was imposed on bottom trawling for around six months, this species of shrimps emerged once again. When the ban was lifted, these shrimps vanished. Fish species such as kumbalawa became next to extinct in the lagoon area,” said Fernando.

With the emergence of trawling, many small scale fishermen engaged in sustainable fishing methods could no longer engage in their profession. Contrary to bottom trawling- where a net bulldozes the seabed with the help of a mechanised bed- traditional fishermen would lay a net in the evening and it remains in the same place till the following morning. “At one point there were eels in abundance and there was a market for eel intestines. But these species became extinct. Dugongs faced a similar plight. But with sustainable fishing practices we believe that crabs and other species would return.

“The government should never think of lifting the ban on bottom trawling. We fought a lot to convince the government to impose this ban in a peaceful manner,” Fernando mused.

Apart from Janasaviyapura, the main livelihood for many people in Vanni Mundalama and Thoradiya is fisheries. “The ban on bottom trawling has in fact provided more employment prospects for people in these areas,” said Saman Nishantha, President of the Thoradiya Fisheries Cooperative. “Most small scale fishermen made a living by catching shrimps. There were around 200-500 boats. But eventually none of these boats went to sea because with bottom trawling almost all of them lost their jobs,” said Nishantha.

He further suggested that the government should impose a ban on tungsten nets as well in order to preserve these resources for future generations.

Sustainable fishing – the way forward

“An estuary is a place where a river flows into the sea - not a lagoon,” Dr. Creech explained further. “There are three rivers that flow in to the Puttalam estuary. Lagoons are shallower, often enclosed bays, where there is a small outlet / inlet and only surface run-off from the land as a source of freshwater,” explained Dr. Creech.

He said that degradation of marine habitats reduce the ecological productivity of the estuary, as does the discriminant harvesting of juveniles of a wide variety of fish, crustacean and mollusc species.

Speaking about sustainable fishing practices, he said that passive forms of fishing - such as gillnets, handlines, longlines - have a much lower ecological impact on marine habitats, non-target species and the target species than active gears (that are pulled, physically encircle) such as trawl nets and purse seines. “The lower the ecological impact of the fishing gear, the more selective the gear is for larger, adult target species, the more likely it is that the fishery can be managed at the maximum sustainable yield. Long story short, the alternative to destructive, indiscriminate active fishing gears like trawl net fishing are passive, selective fishing used by most small scale fishermen.”

Government constrained?

While the debate on a complete ban on illegal bottom trawling in the Indian Ocean especially in the North of Sri Lanka continues from a geopolitical standpoint, fisheries experts such as Dr. Creech observes that the Sri Lankan government’s options to make a meaningful impact to preserve the Indian Ocean ecosystem are quite constrained because of the number of other countries that are actively engaged in harvesting marine resources from the Indian Ocean. “At a regional level the government can continue to support the proposed reduction and eventual phasing out of Fish Aggregating Devices set to harvest yellowfin tuna by the European Union’s fleet of industrial purse fishing vessels. At a national level, the government can continue to encourage Sri Lanka’s multi-day boat owners to live-release protected species of turtles, marine mammals and sharks accidentally caught in offshore and deep-sea gillnet and longline fisheries. At a local level, the government can intervene to improve the management of coastal fisheries to maximise the economic, social and ecological benefits generated by small scale fisheries by enforcing laws that proscribe the use of indiscriminate, destructive fishing fishing gears such as bottom-trawl nets, purse seine and dynamite fishing,” Dr. Creech said in conclusion.