Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Most of us have had an education. But on reflection, this education we had at our schools and outside of it has subconsciously influenced us in the way we judge those whom we encounter during our lives.

Most of us have had an education. But on reflection, this education we had at our schools and outside of it has subconsciously influenced us in the way we judge those whom we encounter during our lives.

I went to St Thomas’ College, Mt Lavinia, which was by any given standard, one of the best schools in Sri Lanka then and it is so even now. Along with other leading schools in Colombo such as Royal College, Ladies College and Bishops College (to name but a few) we considered ourselves to be a cut above the government schools like Visaka, Anula, Ananda and Nalanda simply because of our grasp of the English language and the more affluent backgrounds most of us assumed we came from. This was a given and widely accepted fact. Even though the success rate of those who entered Universities is Sri Lanka were far higher among the Government schools, it was obvious as to why the students in the type of schools that we attended, ended up being fortunate enough to follow up their higher studies abroad, particularly in Oxford, Cambridge, LSE etc. Whilst, privileged played a huge part in our progress, the clamour to be with those who were the ‘right fit’ put on added pressure. Our unconscious affiliations to our colonial past remained strong and ingrained in us.

My alma mater was built on the strong principles of the Church of England. As such, a greater percentage of those who attended this school were from the Christian community. At the start of our day, when we used to walk down past the gates to this most beautiful of schools, we always heard the school choir practising. Our school choir was and still is one of the best in Sri Lanka. It was hearing this choir every single day that has made me appreciate the beauty of choral music. This was an education of the unconscious kind I might add. We began our school day with a daily service (which was in English) and then went back into our classes and mingled with fellow students without even questioning as to why some of them had been left behind from this daily routine. We greeted our teachers with the usual “Good Morning Sir / Miss” and never even thought that “Ayubowan” may have been more appropriate as we were in Ceylon. It took a long time for the penny to drop that not everyone was a Christian. It did also take some time to realize that we were in fact members of a minority community. We had grown up in our own bubble with a yearning for a ‘green and pleasant land’ far away and had totally disconnected from the land we were from.

The stark reality hit some of us smack in the face only after the coalition government of Sirimavo Bandaranayake swept into power. Schools such as ours had to comply and cow down to avoid the threat of nationalisation. We were stuck in a place between Mao’s China and Lenin’s Russia! As soon as this government came in, most of us students were compelled to hard labour under the blazing hot sun, ploughing the beautiful lawns in our school to grow sweet potatoes and manioc to support the national drive for self-sufficiency. Now that we had arrogantly moved out of the Commonwealth and become a ‘Republic’ we did not need any help from the west – did we? To fan the flames even further we had to adapt to a whole new set of die-hard Buddhist teachers who had just joined our staff. These teachers worked totally against the Christian teachers we were accustomed to and formed their own separate clique. Ahubudhhu, Copperehewa, Kolombege, Kalupahane, Edirisinghe et al came into our school with their oil lamps blazing and ready to teach (this privileged bunch) a lesson - in every sense of the word. Suddenly the school hall was being used for lessons in Buddhism.

The stark reality hit some of us smack in the face only after the coalition government of Sirimavo Bandaranayake swept into power. Schools such as ours had to comply and cow down to avoid the threat of nationalisation. We were stuck in a place between Mao’s China and Lenin’s Russia! As soon as this government came in, most of us students were compelled to hard labour under the blazing hot sun, ploughing the beautiful lawns in our school to grow sweet potatoes and manioc to support the national drive for self-sufficiency. Now that we had arrogantly moved out of the Commonwealth and become a ‘Republic’ we did not need any help from the west – did we? To fan the flames even further we had to adapt to a whole new set of die-hard Buddhist teachers who had just joined our staff. These teachers worked totally against the Christian teachers we were accustomed to and formed their own separate clique. Ahubudhhu, Copperehewa, Kolombege, Kalupahane, Edirisinghe et al came into our school with their oil lamps blazing and ready to teach (this privileged bunch) a lesson - in every sense of the word. Suddenly the school hall was being used for lessons in Buddhism.

The Sinhala medium took precedence over the English one, (rightly – I must add - even though it was far too late for most of us) and a Hewisi band replaced the usual western style school band we had. From here on the conflicts within our education began.

At this time the English-speaking Colombo elite retreated into their shells like a bunch of surprised tortoises. Finally, the time for most of our less privileged countrymen and women to claim and celebrate their language and traditions had dawned. As we all now know the effects of Sirimavo’s reign was catastrophic! One of the worst things that happened was the mass exodus of the Burgher community who took off to Australia in droves because they were made to feel distinctly unwelcome. Many of our classmates upped and left. Beautifully maintained colonial style houses in areas of Nugegoda, Dehiwela and Mt. Lavinia were put up for sale as the Burgher population who owned them left in a hurry. Church congregations diminished as did the choirs (as we know most of those Burghers could sing and make music beautifully) and we watched as the lights were being switched off one at a time among the English-speaking households. This left some of us (the English-speaking Sinhalese) isolated, terrified and caught between Mrs. Bandaranayake and the deep blue sea. Looking back at the cultural history of our island prior to this period, it is evident that it was this Burgher community (may they be of Dutch / Portuguese / English or another heritage) who went out of their way to promote what is now recognised as a truly Sinhalese ambiance and feel to our island’s identity. A glance at the legacies of the Bawa brothers, Lionel Wendt, George Keyt, David Painter, Barbara Sansoni etc. and the foundations they laid for a truly unique in their very own fields, says it all. The seeds of division sewn by SWRD Bandaranayake and his call for nationalism were spread further by his ghastly wife. The results of this “Sinhala Only” policy is what has become a recurrent plague that has held back our country ever since. I don’t think I need to enlarge on this anymore.

Those of my age group were placed like pawns in this chess game between this Sinhala-English divide, especially at school and during our leisure activities. The decisions we took about the way we steered our futures was a simple one. Stay or leave.

The melting pot that was Ceylon then, never affected us. All of us came from various ethnic backgrounds and religions, yet none of us wanted to be seen as different to anyone else. We really did not care or bother about the sort of divisions that are visible now. I come from an enormous family where one side was predominantly Buddhist while the other side was Anglican Christian. We also had Roman Catholic, Hindu and Methodist relations connected to us from the Buddhist side of the family. We were effortlessly bilingual and some of us had parents who were trilingual. But the pressure from the groups that we associated with outside of our family circles (be it at school or at leisure activities) added an unseen layer of pressure which had a lot to do with being able to converse in English. Fluency in English remained a key uniting factor outside the comfort zone of our families.

In those days we were very hesitant about communicating in our native language when we in public. We subconsciously looked down on those who conversed in Sinhalese. The tentacles of this bad education had some strange power over us then and remains with most of us even now. I know of quite a few prominent people who really have no time for those who do not speak the Queen’s English, yet they profess to fight for various causes including human rights!

I once mentioned the word “Arangetram” to a Tamil friend who had formerly attended Ladies College. She looked at me as if I was insane. She may die defending her tribe in the North, but her education has misguided her to believe that ballet takes precedence over, “eeew what was that word you mentioned?”

A very close friend of mine is married to a highly artistic woman who speaks her very own brand of English, yet many within our circle simply do not welcome her as an equal. They shun her completely. One person had the audacity to tell her to, “go and learn some English and come back!” This very same toffee-nosed group of English-speakers are always going on about good literature, correct pronunciation, punctuations and diction (which I must admit they are completely right about) but they rarely have any time or energy to help home grown talent. Their support for local writers of plays, novels and poetry etc has always been grudging to say the least. The traditionalists on the other hand have an even bigger problem. There are Sri Lankans all over the world who are experts in various fields but if we take those who have specialized in the fields of arts (especially Dance & Drama), they are never really welcomed back in Sri Lanka as they are seen as a threat to the status co. Any pus-kaapu-suddha can walk in to one of Sri Lanka’s leading dance companies and work with or choreograph for them and these so called “guardians of tradition” will fall at their feet and worship them and accept their instructions as if it’s a god send ONLY because they are white! Dr. Ediriweera Sarachchandra honed on this defect perfectly by saying, “recognition by a foreign body, has in the psychology of the Ceylonese mind, a stamp of authority which no native could hope to give.”

Divisive thoughts were instilled further into us during our teens. Those of us who went to western ballet classes were categorically told that traditional dance forms were for those from the proletariat! The word ‘gode’ was brandished often. We were made to think that traditional drums were tribal instruments more akin to veddas. Our own culture was being torn to shreds in front of our eyes! Unbeknown to us, our westernised education was responsible for damning our own cultural one.

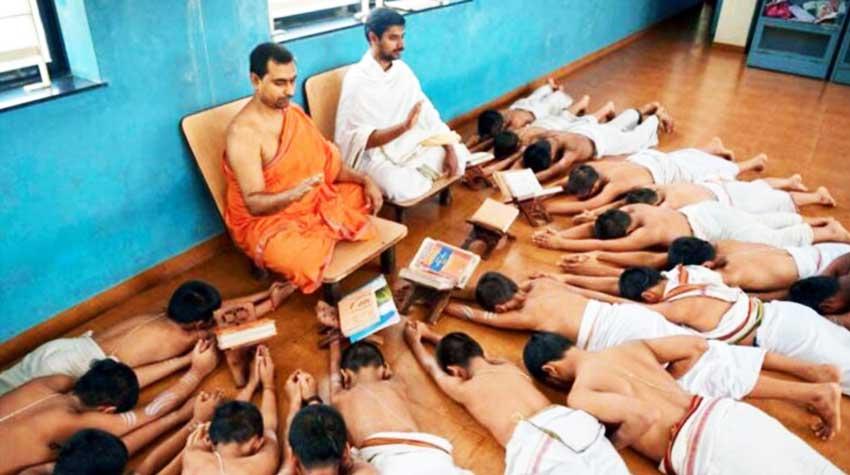

This was countered by those who worked in the traditional art forms especially those in the field of dance. They would look down at us (ballet dancers) and be completely aghast and often referred to us as ‘neecha’ (vulgar). Body contact between male and female performers were a taboo in their minds. Wearing tights without a cloth covering one’s crotch was an act of almost unthinkable vulgarity. This traditional elite who had been pushing their agenda for a ‘Cultural revival’ since 1956 have unfortunately become a voice of chauvinism and a new -Philistinism and all of them exhibit a kind of prudery that cannot be (in my view) anything other than a block on the uninhibited growth the any art form. Their opinion was and still is that the ‘west’ is immoral. The flourishing of Latin American dance in Sri Lanka is a direct reaction to this prudish attitude. After receiving their education in a segregated environment this dance form gives the youth in our country the freedom to dance holding on to someone of the opposite sex. Body contact is legitimised in these classes as its essential and they can wear next to nothing too! The fact that kissing is banned in most Sinhala films is a direct result of this anti-western sentiment held by traditionalists and never the twain has met -yet.

Strangely however, there are those who felt empowered by the possibilities afforded to them by the nationalistic policies begun by those Bandaranayake’s. They have now moved further up on to a new league. Their transition from Salu Sala to Armani was swift. Yet they did not revert to sending their own children to government schools or start wearing traditional garments. Buddhist Sinhalese though they may be their lifestyles reflected nothing of it. They took to the worst of westernized life-styles like flies to shit and they opted for a new swathe of highly expensive International schools for their children. The education at these institutions have only fanned the flames of sense of ‘upstartism’, where one’s worth is measured by the wealth they are seen to have. They do not speak English well and neither do they dare speak in Sinhalese.

A proliferation of those who do not, cannot and will not pronounce ‘not’ or ‘pot’ properly is the result. However, I don’t suppose this, matters anymore. It’s the money that does the talking now.

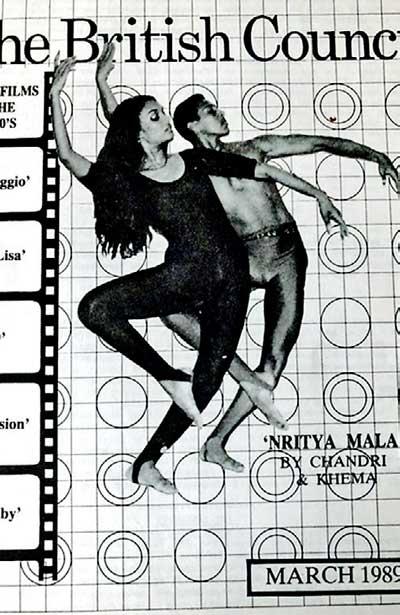

When these divisions between began to simmer. those of us who were caught in this crossfire were still at school. Some of us promptly latch ourselves to English literature and Drama with a renewed vigour. It was also a time when we were prone to exploration. Thankfully, I made a drastic decision and began working with the fabulous traditional dancer Khema. Meeting with her and her wonderful drummers, the late Herath Banda, Dayasila and Guneratne Banda and several of her teachers revealed another world to me. It was the experimental fusing of traditional Kandyan and Low-Country dance forms with western contemporary dance that brought me to the UK, thirty-five years ago. Despite being told about the negative impact of one tradition against the other, the possibilities that something wonderful can come out of knowing both sides is endless. The evidence is out there.

When I was at the Laban Centre, I had the privilege of studying under Valerie Preston-Dunlop PhD. She was a student of Rudolf Laban and pioneered choreology and Labanotation. She told me that the entire point of educating someone is so that they deliberately break the boundaries that are imposed on them and make a student out of their own teacher. Stuart Hopps OBE (my lecturer in choreography) asked me to read Doris Humphrey’s The Art of Making Dances and then told me to, “tear it up – and don’t follow a single word it says.” Teachers in the western world urge you to prove them wrong and challenge you to find new ways of doing things. They encourage you to improve and find your own voice and they certainly do not expect to be treated like gods who demand your lifelong devotion.

Most schools in Sri Lanka have developed tremendously since our time and offer a thoroughly grounded education covering issues relevant to life in the world today. But when it comes to our cultural education it is still very much in the dark ages, this is especially true of the fine arts. Teachers ask for obedience and loyalty. Rivalries, competitiveness, bad mouthing are part and parcel of belonging to one school. Teaching is a jealously guarded commodity. Students are treated like a private army that is mobilised against every other institution that is seen as a rival. Defect and you face the wrath of the teachers. Believe me the verbal and psychological abuse from someone who considers themselves to be your teacher is worse than a firing squad! And all this because you wanted to explore a different avenue of creativity. The problem lies with the educators who tell you what to think and not how to think.

Isn’t it a wonder that we are in the state we are in?